The Arab-Israeli Conflict

A short history in 3,000 words

Also known as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or the Middle East conflict.

Latest update January 16, 2008

-

Ancient history of Israel and Palestine

-

The rise of Zionism

-

The British Mandate for Palestine

-

History of the establishment of the State of Israel

-

The Six Day War and Arab rejectionism

-

History of the struggle for a Palestinian state and the peace process

-

Obstacles to peace

Ancient history of Israel and Palestine

The ancient Jewish kingdoms of Israel and Judea had been successively conquered and subjugated by several foreign empires, when in 135 CE the Roman Empire defeated the third revolt against its rule and consequently expelled the surviving Jews from Jerusalem and its surroundings, selling many of them into slavery. The Roman province was then renamed “Palestine“.

After the Arab conquest of Palestine in the 7th century the remaining inhabitants were mostly assimilated into Arab culture and Muslim religion, though Palestine retained Christian and Jewish minorities, the latter especially living in Jerusalem. Apart from two brief periods in which the Crusaders conquered and ruled Palestine (and expelled the Jews and Muslims from Jerusalem), it was ruled by several Arab empires, and it became part of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire in 1516.

The rise of Zionism

In the late 19th century Zionism arose as a nationalist and political movement aimed at restoring the land of Israel as a national home for the Jewish people. Tens of thousands of Jews, mostly from Eastern Europe but also from Yemen, started migrating to Palestine (called Aliyah, “going up”). Zionism saw national independence as the only answer to anti-Semitism and to the centuries of persecution and oppression of Jews in the Diaspora. The first Zionist congress took place in 1897 in Basel under the guidance of Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl, who in his book “The Jewish State” had painted a vision of a state for the Jewish people, in which they would be a light unto the nations. Zionism basically was a secular movement, but it referred to the religious and cultural ties with Jerusalem and ancient Israel, which most Jews had maintained throughout the ages. Most orthodox Jews initially believed that only the Messiah could lead them back to the ‘promised land’, but ongoing pogroms and the Holocaust made many of them change their minds. Today there are still some anti-Zionist orthodox Jews, like the Satmar and Naturei Karteh groups.

The British Mandate for Palestine

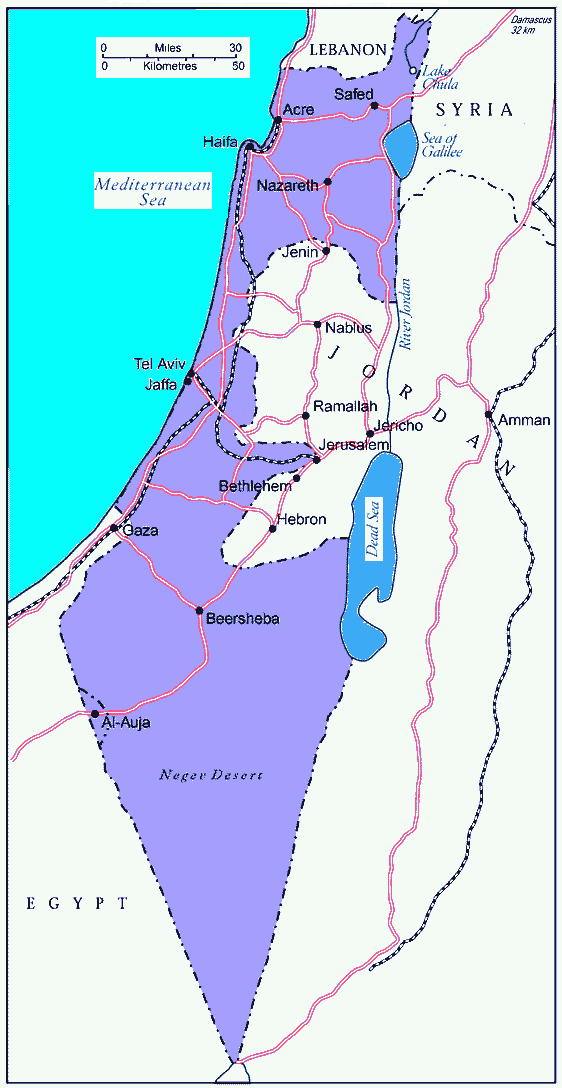

During World War I Great Britain captured part of the Middle East, including Palestine, from the Ottoman Empire. In 1917 the British had promised the Zionists a ‘Jewish national home’ in the Balfour Declaration, and on this basis they later were assigned a mandate over Palestine from the League of Nations. The mandate of Palestine initially included the area of Transjordan, which was split off in 1922 (see map).

Map of the original British Mandate for Palestine and the parts ceded to Transjordan and Syria.

Jewish immigration and land purchases met with increasing resistance from the Arab inhabitants of Palestine, who started several violent insurrections against the Jews and against British rule in the 1920s and 1930s. During the Great Revolt of 1936-1939 the followers of the radical Mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini (a Nazi collaborator who later fled the Nurnberg Tribunal) not only killed hundreds of Jews, but an even larger number of Palestinian Arabs from competing groups. The Zionists in Palestine (called the Yishuv) established self-defense organizations like the Haganah and the (more radical) Irgun. The latter carried out reprisal attacks on Arabs from 1936 on. Under Arab pressure the British severely limited Jewish immigration to Palestine, after proposals to divide the area had been rejected by the Palestinian Arabs in 1937. Jewish refugees from countries controlled by Nazi Germany now had no place to flee to, since nearly all other countries refused to let them in. In response Jewish organizations organized illegal immigration (Aliya Beth), the Zionist leadership in 1942 demanded an independent state in Palestine to gain control of immigration (the Biltmore conference), and the Irgun committed assaults on British institutions in Palestine.

Despite pressure from the USA, Great Britain refused to let in Jewish immigrants – mostly Holocaust survivors – even after World War II, and sent back illegal immigrants who were caught or detained them on Cyprus. Increasing protests against this policy, incompatible demands and violence by both the Arabs and the Zionists made the situation untenable for the British. They returned the mandate to the United Nations (successor to the League of Nations), who hoped to solve the conflict with a partition plan for Palestine, which was accepted by the Jews but rejected by the Palestinians and the Arab countries. The plan proposed a division of the area in seven parts with complicated borders and corridors, and Jerusalem and Bethlehem to be internationalized (see map). The relatively large number of Jews living in Jerusalem would be cut off from the rest of the Jewish state by a large Arab corridor. The Jewish state would have 56% of the territory, with over half comprising of the Negev desert, and the Arabs 43%. There would be an economic union between both states. It soon became clear that the plan could not work due to the mutual antagonism between the two peoples.

Map of the UN Partition Plan for Palestine, November 1947.

History of the establishment of the State of Israel

[See also: “Timeline: Israel War of Independence“]

After the proposal was adopted by the UN General Assembly in November 1947, the conflict escalated and Palestinian Arabs started attacking Jewish convoys and communities throughout Palestine and blocked Jerusalem, whereupon the Zionists attacked and destroyed several Palestinian villages. The Arab League had openly declared that it aimed to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state by force, and Al Husseini told the British that he wanted to implement the same ‘solution to the Jewish problem’ as Hitler had carried out in Europe.

A day after the declaration of the state of Israel (May 14, 1948) Arab troops from the neighboring countries invaded the area. At first they made some advances and conquered parts of the territory allotted to the Jews. Initially they had better weaponry and more troops, but that changed after the first cease-fire, which was used by the Zionists to organize and train their newly established army, the Israeli Defense Forces. Due to better organization, intelligence and motivation the Jews ultimately won their War of Independence.

After the armistice agreements in 1949, Israel controlled 78% of the area between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean Sea (see map below), whereas Jordan had conquered the West Bank (until then generally referred to as Judea and Samaria) and East Jerusalem and Egypt controlled the Gaza Strip.

Jerusalem now was divided, with the Old City under Jordanian control and a tiny Jewish enclave (Mount Scopus) in the Jordanian part. In breach of the armistice agreement Jews were not allowed to enter the Old City and go to the Wailing Wall. In 1950 Jordan annexed the West Bank and East Jerusalem, a move that was only recognized by Great Britain and Pakistan. A majority of the Palestinian Arabs in the area now under Israeli control had fled or were expelled (estimated by the UN about 711,000) and over 400 of their villages had been destroyed. The Jewish communities in the area under Arab control (i.a. East Jerusalem, Hebron, Gush Etzion) had all been expelled. In the years and decades after the founding of Israel the Jewish minorities in all Arab countries fled or were expelled (approximately 900,000), most of whom went to Israel, the US and France. These Jewish refugees all were relocated in their new home countries. In contrast, the Arab countries refused to permanently house the Palestinian Arab refugees, because they – as well as most of the refugees themselves – maintained that they had the right to return to Israel. About a million Palestinian refugees still live in refugee camps in miserable circumstances. Israel rejected the Palestinian ‘right of return’ as it would lead to an Arab majority in Israel, and said that the Arab states were responsible for the Palestinian refugees. Many Palestinian groups, including Fatah, have admitted that granting the right of return would mean the end of Israel as a Jewish state. The question of the Palestinian right of return is the first mayor obstacle for solving the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Map Israel within the Green Line 1949-1967.

The Six Day War and Arab rejectionism

The Arab-Israeli conflict persisted as Arab countries refused to accept the existence of Israel and instigated a boycott of Israel, while they continued to threaten with a war of destruction. (There were some talks, but the Arab states all demanded both the return of the refugees and also parts of Israel in return for just non belligerence). They also founded Palestinian resistance groups which carried out terrorist attacks in Israel, like Fatah in Syria in 1959 (under the guidance of Yasser Arafat), and the PLO in Egypt in 1964.

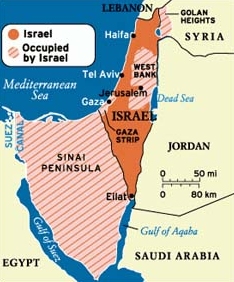

In May of 1967, the conflict escalated as Egypt closed the Straits of Tiran for Israeli shipping, sent home the UN peace keeping force stationed in the Sinai, and issued bellicose statements against Israel. It formed a defense union with Syria, Jordan and Iraq and stationed a large number of troops along the Israeli border. After diplomatic efforts to solve the crisis failed, Israel attacked in June 1967 and conquered the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Desert from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria and the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan (see map below). Initially Israel was willing to return most of these territories in exchange for peace, but the Arab countries refused to negotiate peace and repeated their goal of destroying Israel at the Khartoum conference.

Map Israel after Six Day War 1967.

The Six Day War brought one million Palestinians under Israeli rule. Israelis were divided over the question what to do with the West Bank, and a new religious-nationalistic movement, Gush Emunim, emerged, that pushed for settling these areas.

After 1967 the focus of the Palestinian resistance shifted to liberating the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as a first step to the liberation of entire Palestine. The Arab Palestinians started to manifest themselves as a people and to demand an independent state. East Jerusalem, reunited with West Jerusalem and proclaimed Israel’s indivisible capital in 1980, but also claimed by the Palestinians as their capital, became a core issue for both sides in the conflict. The division of Jerusalem with its holy places is the second large obstacle for a solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict.

History of the struggle for a Palestinian state and the peace process

In 1974 the PLO was granted observer status in the UN as the representative of the Palestinian Arabs. Beside the UNRWA (set up in 1949 for relief of the Palestinian refugees) several new UN institutions were established to support the Palestinians and their struggle for their own state. In 1975 the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 3379, declaring Zionism to be a form of racism, which caused the UN to lose its last bit of credibility as a neutral mediator in the eyes of Israel, although that resolution was ultimately revoked in 1991. Former UN actions perceived as bias by Israel included the establishment of UNRWA as a separate organization aimed at assisting but not repatriating the Palestinian refugees and the easy acceptance of Egypt’s decision to dismiss the UN peacekeeping force from the Sinai. The ‘Zionism is racism’ resolution gave a strong boost to the settlers’ movement and helped bring the rightwing Likud party to power in 1977.

In 1979, under Likud prime minister Menachem Begin, Israel and Egypt signed a peace treaty after American mediation, for which Israel returned the Sinai Desert to Egypt. Subsequent negotiations regarding autonomy for the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank failed because the Palestinians didn’t accept Israel’s limited autonomy proposal for these areas, and Israel refused to accept the PLO as a negotiation partner. This changed in the early 1990s after the PLO had renounced violence, recognized the legitimacy of Israel, and declared to only strive for a Palestinian state in the 1967 occupied areas. Moreover a major uprising of the Palestinians in the occupied territories from 1987 on (the first Intifadah) convinced the Israeli government that they could not continue to rule over the Arab population. Partly secret negotiations in Oslo led to an agreement under which in 1994 a Palestinian National Authority was established under the leadership of Arafat and the PLO, to which Israel would gradually transfer land. Elections were held for the presidency of the PNA and the Palestinian Legislative Assembly, from which violent or racist parties were excluded. After a 5 year transition period the most difficult matters would be settled in final status negotiations, such as the status of Jerusalem, the Palestinian refugees, the Jewish settlements and the definite borders. Eventually 97% of the Palestinians came under PA control, including all of the Gaza Strip and approximately 40% of the West Bank land.

Since 1967 Israel has been establishing Jewish settlements in these areas, at first mostly small ones in unpopulated areas and under the Likud governments from the late 1970s on all over the area and large settlement blocs. Although the Oslo agreements did not require removal of the settlements, it was clear that they would constitute an obstacle to a definite peace agreement. The rapid growth of the settlements undermined Palestinian confidence in the peace process. The Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, who partially froze settlement construction, was assassinated by a Jewish extremist in 1995.

On the Palestinian side, Israeli withdrawal from Palestinian territory led to the construction of a terror network by the extremist Hamas and other groups, who from the mid 1990s on were able to carry out an unprecedented number of suicide attacks inside Israel. Under Arafat the PA took limited action against the terror groups and even funded them, and Arafat gave the green light for attacks when that suited his strategy. The continuing violence by Palestinian extremists constitutes the fourth obstacle for peace.

The Oslo peace process got bogged down because both the Palestinians and the Israelis did not stick to agreements they made and the leadership on both sides did little to build confidence and to prepare their own people for the necessary compromises. Large groups on both sides protested against the concessions required by the agreements made. The peace process slowly dragged on towards the negotiations on Camp David in the summer of 2000. After the failure of Camp David a provocative visit to the holy Jerusalem Temple Mount by Likud leader Ariel Sharon sparked the second Intifada, which the Palestinian Authority had been preparing for. Palestinian leaders like Marwan Barghouti later admitted to having planned the second Intifada in the hope that it would press Israel into more concessions. However, the opposite happened, as the Israeli peace camp collapsed under the violence of Palestinian suicide attacks.

In December 2000 US president Bill Clinton presented “bridging proposals” suggesting the parameters for a final compromise, including a Palestinian state on all of the Gaza Strip and about 97% of the West Bank, division of Jerusalem and no right of return to Israel for Palestinian refugees. While Israel in principle accepted this proposal, no clear answer came from the Palestinian side. In last minute negotiations at Taba in January 2001, under European and Egyptian patronage, the sides failed to reach a settlement despite further Israeli concessions. Both sides agreed to a joint communiqué saying they had never been so close to an agreement, but substantive disagreements remained about i.a. the refugee issue.

Shortly after that Sharon’s Likud party won the Israeli elections, and in the US democratic president Bill Clinton was replaced by George W. Bush. Following the terrorist attacks from Al Qaida inside America on September 11, 2001, Bush permitted Sharon to strike back hard against the second Intifada. After suicide attacks had killed over a hundred Israelis in March 2002, Israel re-occupied the areas earlier transferred to the Palestinian Authority and set up a series of checkpoints, which severely limited the freedom of movement for the Palestinians. In 2003 Israel started the construction of a very controversial separation barrier along the Green Line and partly on Palestinian land. These measures led to a strong decline of Palestinian suicide attacks in Israel, but also to international condemnations. Especially the dismissal of Palestinian workers in Israel led to increasing poverty in the territories.

Although both parties accepted the ‘Road Map to Peace‘, launched by the Quartet of US, UN, EU and Russia in 2003, no serious peace negotiations have taken place in recent years between Israel and the Palestinians. Israeli PM Ariel Sharon did take unilateral measures such as the disengagement from the Gaza Strip in 2005, but he demanded an end to Palestinian terrorism before he would engage in negotiations with Arafat’s successor Abbas concerning final status issues. Plans for further unilateral withdrawals from the West Bank were put on ice after Hamas won the PA elections in early 2006, thousands of rockets were fired from the Gaza Strip into Israel, and border attacks took place from both the Gaza Strip and south Lebanon (which Israel had unilaterally withdrawn from in 2000). The latter had spurred the disastrous Second Lebanon War in the summer of 2006.

Obstacles to peace

The primary cause for the Arab-Israeli conflict lies in the claim of two national movements on the same land, and particularly the Arab refusal to accept Jewish self-determination in a part of that land. Furthermore fundamentalist religious concepts regarding the right of either side to the entire land have played an increasing role, on the Jewish side particularly in the religious settler movement, on the Palestinian side in the Hamas and similar groups. But whereas the settlers received a blow when they failed to prevent the disengagement from the Gaza Strip, Hamas won the Palestinian elections, and after their breakup with Fatah and their take-over of the Gaza Strip, they remain a dominant force capable of blocking any peace agreement.

The Arab-Israeli conflict is further complicated by preconceptions and demonizing of the other by both sides. The Israelis see around them mostly undemocratic Arab states with underdeveloped economies, backward cultural and social standards and an aggressive religion inciting to hatred and terrorism. The Arabs consider the Israelis colonial invaders and conquerors, who are aiming to control the entire Middle East. There is resentment concerning Israeli success and Arab failure, and Israel is viewed as a beachhead for Western interference in the Middle East. In Arab media, schools and mosques anti-Semitic stereotypes are promoted, based on a mixture of anti-Jewish passages in the Quran and European anti-Semitism, including numerous conspiracy theories regarding the power of world Zionism.

Since the Oslo peace process however, a broad consensus has been formed that an independent Palestinian Arab state should be established within the areas occupied in 1967. Polls on both sides show that majorities among Israelis and Palestinians accept a two state solution, but Palestinians almost unanimously stick to right of return of the refugees to Israel, and most Israelis oppose a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem.

Some articles in English about the history of the Arab-Israeli conflict on this website

- Britain and Balfour: The Palestine Mandate – by Joseph Dunner

- Zionism and its Impact – Effect of Zionist Settlement on Arab Palestinian Economy and Society

- Palestinian Refugees, Expulsion or Flight?

- A Personal Exodus Story (A Jewish Refugee from Egypt)

© This article is copyright Israel-Palestina Informatie, aside from the maps and other parts that mention outside sources. For permission to copy our materials please contact us through our e-mail address. Limited citations accompanied with a link to this website are allowed.

Some internet sources used for this article

- A History of Zionism and the Creation of Israel, Zionism and its Impact, Arab Revolt in Palestine (“The Great Uprising”) 1936-1939 and other pages on Zionism and Israel Information Center

- Maps from i.a. World History at KMLA, Historical Atlas of the Twentieth Century and MidEastWeb – Middle East Maps

Other recommended websites on Israel – Palestine and the Middle East Conflict

- A Brief History of Israel and Palestine and the Conflict, The Early History of Zionism and the Creation of Israel, and many other articles on MidEastWeb for Coexistence – Middle East news & background, history, maps and opinions

- Wikipedia categories Israel and Zionism, Palestine and Middle East

- Peace and Security Association (Israel)

- One Voice Movement

- Ariga’s PeaceWatch – on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and Middle East peace

- Middle East Analysis

- Israel News

- Israel: Like This, As If (blog)

- Zionism and its Impact and other articles on Zionism and Israel Information Center

- ZioNation – Progressive Zionism and Israel Web Log

- Israël Informatie Linkpagina (Dutch / English)

- Israël & Palestijnen Nieuwsblog (Dutch / English)

http://www.israel-palestina.info/arab-israeli_conflict.html A short History of the Arab-Israeli conflict